Delhi assaults the senses. It’s polluted, noisy, smelly and can look as rough as fuck but just when you think you can’t take it anymore, there are glorious gardens and majestic temples that restore one’s faith in the city.

Many are in the districts to the south of the historic centre, in New Delhi, Mehrauli and South Delhi, where things are a little bit calmer and it’s easier to appreciate what the capital has to offer. Several centuries ago these areas were green and pleasant lands, where the rich and famous could live in comfort and rest in peace. Palaces and tombs stood alone, where now they’re surrounded by the modern city.

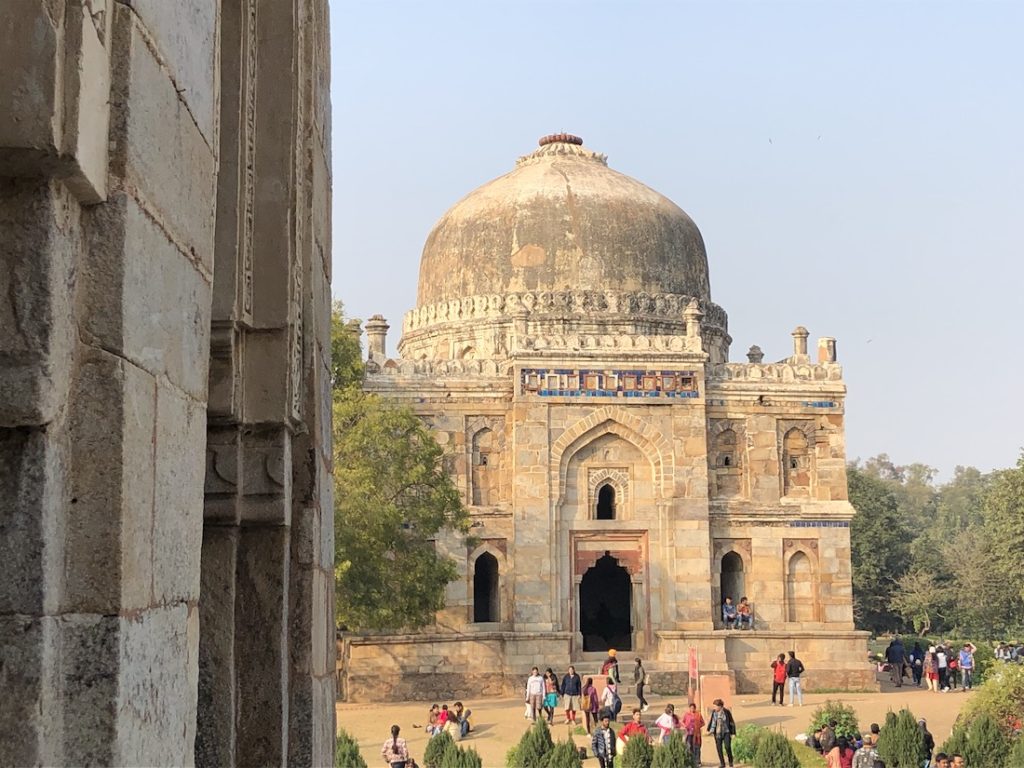

The Lodi Gardens is one of the best green spaces in New Delhi, deep in one of its most affluent districts. They’re punctuated by a number of tombs and mosques built by the Lodis, who ruled parts of northern India in the 15th and 16th centuries before the arrival of the Mughals. The acres around the tombs were landscaped in the 1930s under the direction of Lady Willingdon, wife of the then British Viceroy, to include shrubs, trees, lakes and lawns. Our trusty Lonely Planet told us they would be a peaceful retreat from the noise and drama of the city but on our weekend visit they were heaving with people – families, young lovers, groups of friends and classes of school children. By the looks of it, most visitors had dumped the rubbish from their picnics on the lawns and flowerbeds and I was appalled by their laziness and disrespect for the environment. India is without doubt the most litter-strewn country I’ve visited, worse even than The Lebanon – and that’s saying something. I felt sorry for the litter pickers, who faced a nigh-on impossible task trying to keep the waves of rubbish under control and went about their task with a subdued resignation.

Despite the rubbish, the grounds are lush and attractive, the tombs superb and I couldn’t help thinking that it was a miracle they’d survived the centuries so intact. We wandered about, admiring the architecture, intricate carvings, fretwork and decoration on the tombs of Mohammed Shah and Sikander Lodi in particular, dodging the numerous impromptu games of cricket being played by boys old and young. In the centre of the park is the Bara Gumbad, a big domed structure and a three-domed mosque built during the reign of Sikander Lodi in the late 15th century. Further on, Sikander’s tomb is surrounded by battlements, which shelter it from the crowds and help make it a peaceful and architectural highlight of the park. In Britain we’d pay a tenner each to visit anything like it, there’d be a shop and aged Tory women to show us round. In Delhi it’s free, and there’s no souvenirs to buy.

We took time to appreciate the architecture and landscapes but most of the visitors were more interested in having their photos taken against an endless range of photogenic backdrops, posing self-consciously. It’s the tragedy of the selfie generation that in the rush to get from one gorgeous location for a photo to another they’re missing out on the great stories from history and some wonderful buildings. We walked back to the modern Metro station through one of the city’s poshest areas, full of swanky colonial-era bungalows, towering trees, embassies and wide, leafy streets – a huge contrast to Old Delhi. Even the car horns were few and far between.

The Lodi tombs are impressive but nowhere near as spectacular as Humayun’s tomb in South Delhi. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, it was commissioned in the 16th century by the Mughal Emperor’s wife and is widely considered to be the architectural precursor of the majestic Taj Mahal, built later by one of his successors, Shah Jahan. It’s an astonishing building, in the red sandstone and white marble that is such a trademark of the Mughals, and became the final resting place of many of Humayun’s family and descendants. The grounds are beautiful, shaded and green, and feature several other buildings. Most notable of them is the tomb and mosque of Isa Khan, a leading court noble who died in the mid 16th century. We wandered among its arches and gardens, which were largely free of people, admiring the decoration.

But it’s Humayun’s tomb that really takes the proverbial breath away. Walking through its gatehouse, the tomb reveals itself in the middle of a typically symmetrical Islamic paradise garden. The building is much larger than I’d imagined, dominated by a white marble dome, rich in beautiful carvings, relief work and perfect arches. The tomb sits above the gardens, reached by several flights of stairs, but inside isn’t much to write home about. Out front, the grounds were full of visitors and yet more schoolchildren in smart uniforms, many of whom wanted to shake our hands or have their pictures taken with me. To get away from the throng we walked through the grounds, circling the building, appreciating it in quieter surroundings. It’s an amazing place, one that reveals the astonishing craftsmanship, imagination and skills of the Mughals.

Early on in the day I’d felt ill but as the day wore on I recovered and so we found ourselves a taxi driver who’d take us on to the extraordinary Qutb Minar complex in the south-west of the city. Another UNESCO World Heritage Site, the site includes a mammoth minaret, a mosque and other structures dating from the glory days of the Delhi Sultanate, which ruled much of the sub-continent in the Middle Ages. Despite it being later in the afternoon, the queues at the ticket booth were tediously long, revealing just how inpatient many Indians can be in a crowd. Fortunately, security guards were on hand to keep the pushers and shovers in check.

Things were a bit calmer inside the grounds, which are dominated by that huge 73m minaret – the Qutb Minar – built in red sandstone and marble, and covered in beautiful carvings. Construction began in about 1192 and additional storeys were added in subsequent years. How it’s survived war, earthquake and thievery I’ll never know but I’m glad it has because standing at its foot and looking up to its peak is an experience beyond description. Astonishingly, the remains of an attempt to build an even bigger minaret stand not far away.

We visited plenty of other buildings on the site but most are ruins, including mosques, tombs and majestic gateways. However, they’re full of atmosphere and it’s still possible to appreciate the workmanship that went into them, for some of the stonework is exceptional. Quite how the arrogant, Victorian, colonial British could argue that the Indians were backward barbarians is beyond me.

We left for the drive back to our hotel, Le Meridien, along urban motorways jammed with commuters, tuk tuk drivers and motorcyclists, quite a few of whom possessed what could best be described as a death wish. Food stalls lined the carriageways, some seedy and others tempting, cattle meandered and buildings cluttered the skyline in a riot of colour.

That night we ate a fine meal at atmospheric Chor Bizarre in stylish Bikaner House, just beyond the India Gate in Raj-era New Delhi. Surrounded by antiques, we dined on delicious local lamb and chicken dishes, quaffed a passable Indian Sauvignon Blanc and appreciated the quality of the service. By the look of it we were lucky to get a table because it was very busy indeed. Our last night in town saw us dining in a very different place, in the Art Deco splendour of The Imperial Hotel on Janpath. It’s one of those hotels I’d loved to have stayed in during our Indian trip but it was far too expensive for our budget, the sort of place populated by pensionable-age Brits who’ve yet to come to terms with the end of Empire, aged American women who’ve spent too much on facelifts and snooty European countesses with vexing toy dogs. It was gorgeous and faultless inside and we opted for the pricey Italian restaurant, San Gimignano, where we feasted on some hearty plates of pasta, because the next day we were off to Agra by train and the last thing I wanted was the sort of gut problem associated with fiery Indian grub…

Delhi had been fascinating, punishing, wonderful and awful. It was time to find out whether Agra would be the same.