Quebec’s largest and most energetic city has a charming old town, great bars and restaurants, but also a touch of the chaotic about it.

It’s not a city that’s easy to fall in love with. Much like Toronto, it feels like it’s been thrown together with little thought to the whole. A motorway ploughs through its heart, generating clouds of fumes, there’s a depressingly large number of homeless people, and road works and closures appear to be the norm rather than the exception. Much of the architecture is unremarkable, litter collection is low on the list of priorities and I got the impression that anyone could do anything to their properties regardless of the planning laws.

But there’s plenty on the plus side too. In late April and early May, as Canada opened up to tourism after the Covid-19 pandemic, the city was full of energy and spring was bursting out after the cold and gloom of winter. Outdoor seating was going up outside bars and cafes and windows were open for the first time in months. At the Marche Atwater, a grand market west of Downtown, stallholders had stocked up on an impressively large range of garden plants ready for the seasonal rush. So despite having a stinking cold and having to wear a mask a lot of the time, we did plenty of walking, eating and drinking (although I couldn’t taste a thing), visited a few sights and were charmed by the French-speaking locals.

For such a large city, there’s not a particularly impressive range of tourist attractions, at least the type that would have us parting with our cash. Perhaps a lot of heritage was wiped out as the city expanded to meet the demands of a growing population and economy, to be replaced by the uniform or just plain ugly. This is a city that’s long been seen as the gateway to Canada for the many immigrants who built the country over the generations, but there’s not a lot to celebrate it in the same way as New York’s Tenement Museum or Singapore’s Chinatown Heritage Centre.

Montreal is more a city to absorb on long walks around its many neighbourhoods, soaking up the atmosphere, the quirkiness, the smells and sounds. A walk round the old town revealed a collection of attractive stone buildings from the city’s earliest days, many betraying the French heritage of its early settlers. Chateau Ramezay was built in 1705 as a residence of the Governor of Montreal but over the years has had a number of other functions, including a school. Today it’s a museum that surveys the city’s history and, although at times it’s a bit dry and old-fashioned, at least it doesn’t ignore the fact that Europeans took the land from the indigenous people. It has a celebrated garden but it was still recovering from winter during our visit.

Round the corner is the vibrant Place Jacques-Cartier, which leads to the unremarkable Old Port. As a square it’s a bit too touristy but it has some handsome buildings and Montreal’s own version of Nelson’s column (clearly a case of rubbing French noses in it). It leads into Rue St Paul Ouest, which is one of Montreal’s oldest and finest streets. On stretches of it and its side roads are some of the city’s best boutiques, bars and restaurants; where we hung out at the Wolf and Workman pub on several afternoons and evenings, enjoying their craft ales, and stayed at both the Hotel Bonaparte and Le Petit Hotel. It’s an area where galleries display breathtakingly bad art and clothes shops are a cut above the chain stores.

The nearby Pointe-à-Callière history and archaeology museum strips back the layers of old Montreal to reveal its foundations below street level. We’ve been to many similar museums over the years, often with archaeology dating to the Roman era and earlier. In Montreal it’s all a bit more recent but fascinating and well done regardless. The highlight is walking through the (once) main sewer that drained the young settlement.

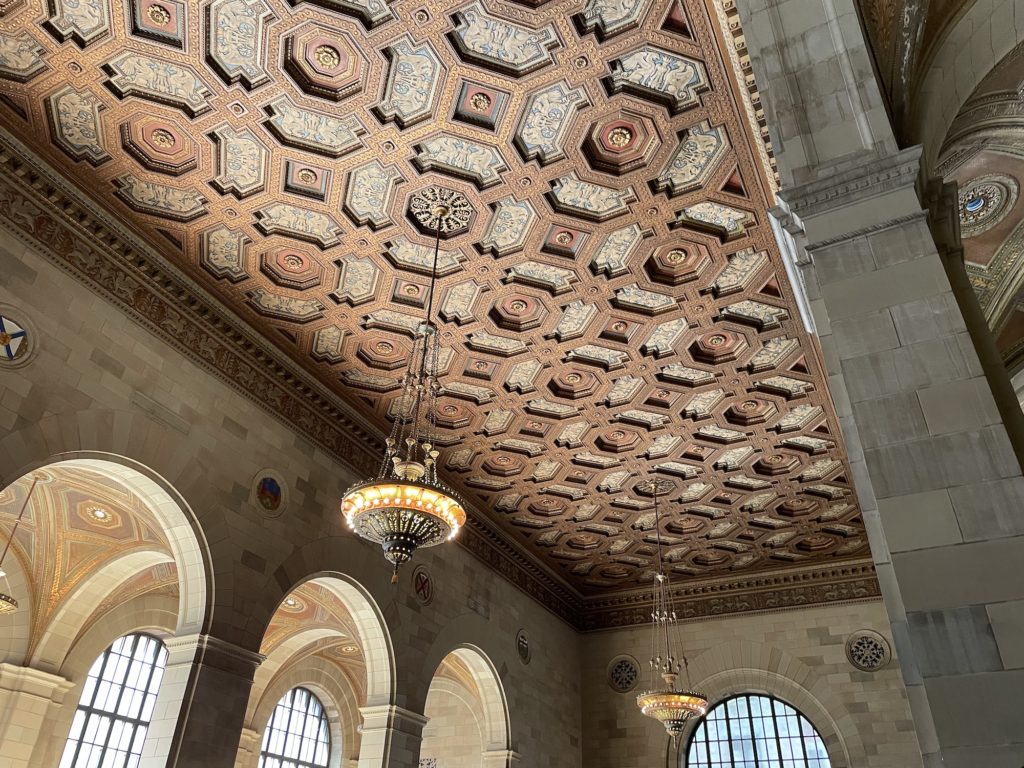

The Place D’Armes, with its statue of city founder Paul de Chomedey, is the city’s principal square, dominated by Notre-Dame Basilica and some excellent Art Deco era offices. This leads to Downtown and the monumental Victorian / early 20th century blocks built to glorify mammon, the preserve of bankers and merchants. It’s the type of architecture you’d find in Wall Street and the City of London and a fine example is the glamorous 1920s Royal Bank Tower, which now has a trendy cafe and co-working spaces in the old banking hall. The elegant teller counters remain behind the modern clutter, overlooked by grandiose memorials to bank employees who died in the wars of the 20th century and beneath a coffered ceiling featuring Wedgwood porcelain tiles that wouldn’t look out of place in a king’s palace. Of an evening, round the corner, we stopped a few times at the friendly Pub St-Pierre.

We visited a few other neighbourhoods recommended by the Lonely Planet guidebook and started one walk at Carré Saint-Louis Montréal, a quiet spot off busy Rue St Denis with some colourful Second Empire homes, the type that turn up all over the city. We explored some of the streets in the Plateau Mont-Royal district but it was all a bit drab and shoddy. We ended further south on Rue St Denis, near the Université du Québec à Montréal, which is full of bars and restaurants – many of them cheapo. Fortunately, there’s a branch of the brewery Le 3 Brasseurs there and it saved us from the gaudy and average with its quality beer.

The Gay Village is nearby and is also a bit of a dump. It has the look of one of those dull London suburbs that was blown to bits during the war and then lumbered with unimaginative, boxy replacement buildings of little or no merit. There were the usual range of bars, from the smart to the sleazy, but I found it rather depressing.

We took the metro out to the Montreal Botanical Garden, one of the largest in the world, but being early spring it was only just showing signs of life. The Chinese garden was being renovated and the Japanese garden lacked the impact of others. However, the sweaty glass houses had some exceptional displays of bonsai, cacti and rain forest plants, and the Alpine Garden was full of meandering paths amid the rocks and planting and looked great beneath a deep blue sky.

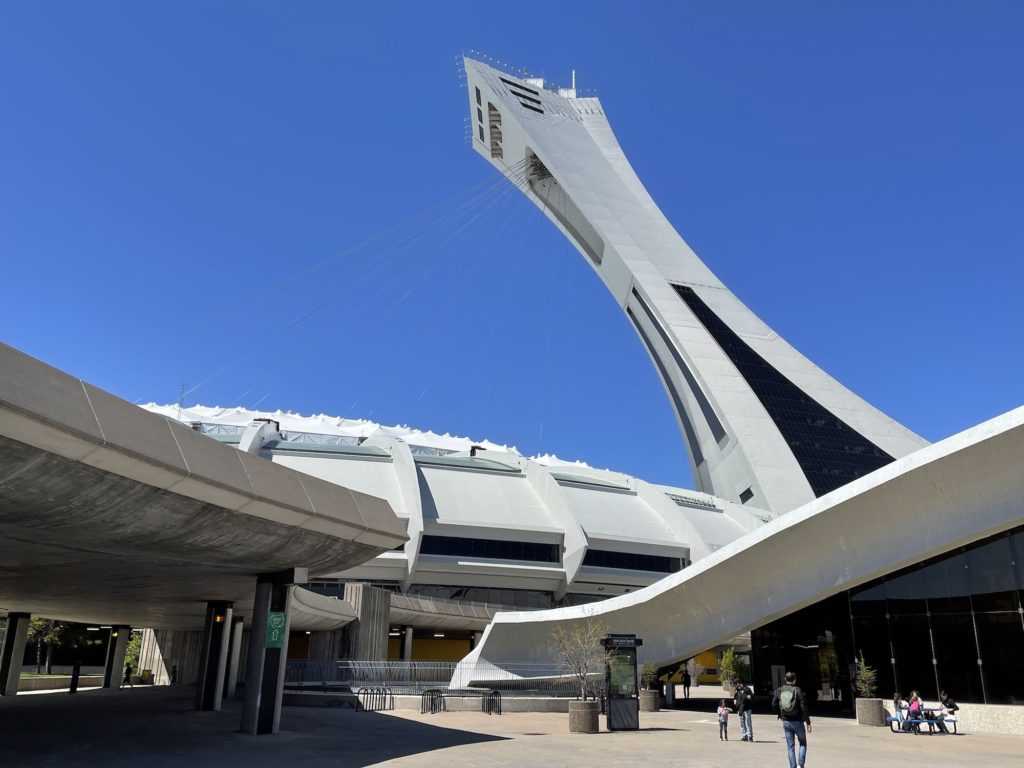

Just over the road is the 1976 Olympic Park with the sort of spectacular 1970s futuristic architecture that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a sci-fi movie of the era. The inclined Montreal Tower looms over it all and can be seen for miles but the old velodrome has been converted into the BioDome, featuring an indoor collection of natural habitats – a tropical forest, the Laurentian forest, the St Lawrence Marine Ecosystem and the Sub-Polar Region. It’s fine for an hour or two but this is mainly kids’ stuff because the domes don’t just focus on flora but have fauna too, making it something like a cross between an Eden Project dome and a zoo. And as you get with animals, most of the time they want to sleep well out of sight of over-excited young humans. Still, who isn’t transfixed by the sight of penguins playing?

The similarly named Biosphere on the Ile St Helene is a survivor of the 1967 Expo. It served as the USA Pavilion but was donated to the city after the expedition closed and is now an Environment Museum. The star of the show is the structure itself, a geodesic dome with great views of the city and port, while the museum itself is slick but surprisingly unengaging.

We concluded our stay in Montreal with a trek around the substantial hill that gives the city its name, the Mont Royal. It was hot and sunny so the trees that smother its slopes provided valuable shade, as did my new Panama hat purchased at the venerable Montreal institution Henri Henri earlier in our stay. Joggers, hikers and cyclists were out in force and Graham bravely made the climb all the way up the long flight of stairs to the Kondiaronk Belvedere to take in the views. I remained firmly attached to a seat at the bottom…

The path eventually led us to the Westmount district, which is clearly where all the money is. The quiet, tree-lined streets are lined with impressively large homes, with immaculate gardens and twitching curtains. Well-behaved school children passed by, litter was notable by its absence. A completely different Montreal…