The ancient Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacán has striking pyramids and grand avenues, yet little or nothing is known of the civilisation responsible for its construction. But whoever they were, you can’t fault the scale of their ambition. The city contains the third largest pyramid ever built – the mighty Pyramid of the Sun – and a collection of other architectural wonders.

Teotihuacán is an easy hour-long journey from Mexico City’s modern Autobuses del Norte bus station, and lies north-east of the endless urban sprawl of the ever-expanding capital, its jammed freeways and cable car networks. But it’s not such an easy place to explore on a hot day as it sits in a dusty, sun-drenched and shade-free bowl, surrounded by hills; there’s a lot of walking and many steps to conquer in order to explore the entire site.

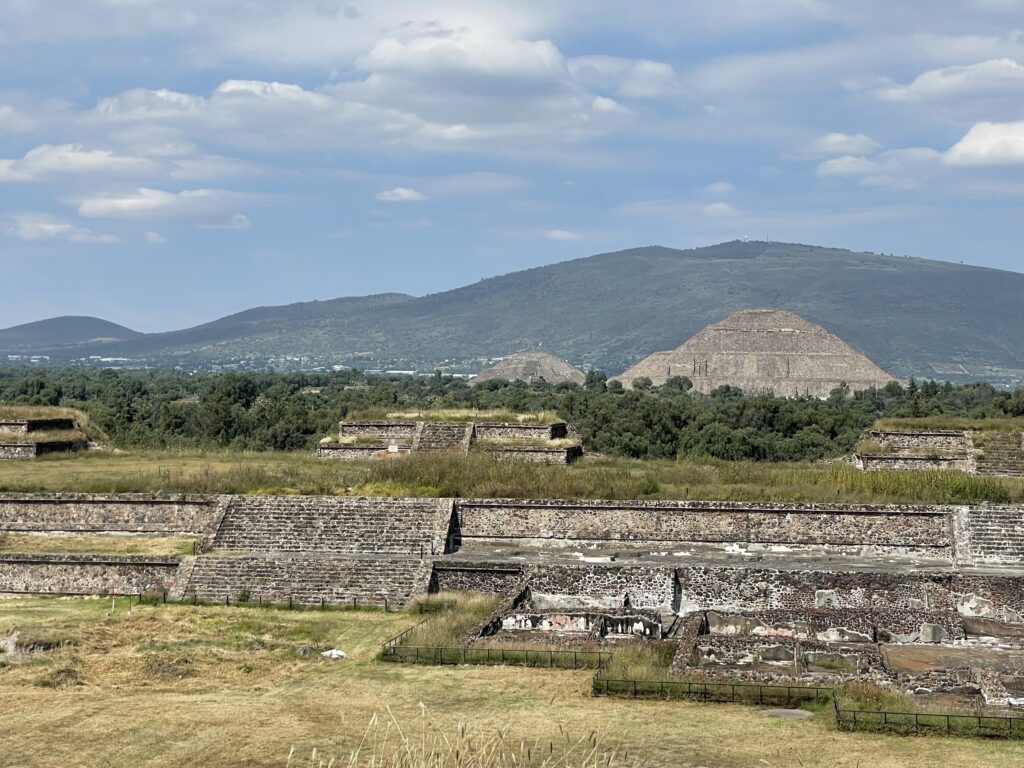

The Pyramid of the Sun sits slap bang in the middle of the view from Gate 2, where the bus dropped us, although the impact of it is lessened by a drab car park and an avenue of vendors. They are pretty much everywhere else on site too, selling their obsidian trinkets, costume jewellery and painted skulls, sheltering from the heat beneath sheets and sun-hats.

Teotihuacán, one of Mexico’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites, was first settled by scattered farmers in around 600BCE and developed slowly over the centuries into an imposing city. It wasn’t until the period 1CE to 350CE, when it boomed to become the largest in Mesoamerica, that its magnificent pyramids, other monumental structures and grand avenues were built. The city and its leaders wielded great power over the region but, just three or four centuries later, decline set in and and other cities and regions started to overshadow it. Teotihuacán continued to be occupied and civilisations, including the Aztecs, came and went but it was never the same and much of it became consumed by nature. Archaeologists have uncovered just a part.

The Pyramid of the Sun – a name given to the structure by the Aztecs – is awe-inspiring. It was built in stages above a network of caves and tunnels, rising ultimately to almost 75m, and was once topped by a temple that was integral to the worship of a deity. In its heyday it was finished in plaster and decorated with brightly coloured murals, only hints of which remain. Today, heavy and grey in the landscape, it’s impossible to imagine the impact it would’ve had on visitors to the city.

We wandered up the Avenue of the Dead, another name stamped on the city by the Aztecs who wrongly assumed it was lined with tombs, towards the smaller but no less imposing Pyramid of the Moon. Those supposed tombs were, in fact, residential blocks and smaller pyramids. A surviving mural of a jaguar adds a splash of colour and is remarkably well preserved. The Pyramid of the Moon dominates a grand plaza complete with central altar and the whole is overshadowed by the hill beyond called Cerro Gordo, which the pyramid is said to imitate in shape. Like its larger sister, the pyramid we see today was the last of several, built atop previous incarnations like a Russian doll. It was another important religous structure, site of ceremonies and sacrifices, and many treasures and skeletons of animals and humans were found during excavations.

To one side of the vast plaza is the Palace of Quetzalpapálotl, which also dates from the heyday of Teotihuacán and was probaby home to an important priest or civic leader. Some colourful murals of jaguars and carvings of mythological birds survive amid the complex of rooms above and below ground, which weren’t properly excavated until the 1960s.

With the heat building, we started the long trek down the Avenue of the Dead towards The Citadel at the other end of Teotihuacán. Most don’t make it to the end of the 2.5km sacred road, thanks to the heat, the steps and the obstacles. Either side, more remains of buildings can be explored but they are but a fraction of the old city. Nature has long since overtaken the rest, smothering the past with cacti, trees and pretty wildflower meadows. Countless butterflies danced around the site hunting for food and a mate, gathering in great clouds where the ground offered a hint of moisture.

The on-site museum, nestled in a modest garden, provided a welcoming respite from the heat and hosts an impressive collection of finds, including relocated burials, frescoes and statues.

The Citadel – a name given to the vast courtyard development by the Spanish – sits at the southern end of the excavated site and is so large it could’ve easily housed around 100,000 residents of the city. Its principal feature is the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the third largest pyramid, and the greatest surprise of all of Teotihuacán’s treasures. The western facade is mainly hidden from view at ground level by another structure called the Adosada. We had to climb it’s scarily steep steps to view the temple in all its glory, and I’m very glad we did. There, on the pyramid’s facade, are a collection of monumental carvings of the feathered serpent that we sat and admired for some time, trying to ignore a group of gormless Americans not far away who were inexplicably ranting at each other. Archaeologists founds many treasures buried under the pyramid, as well as dozens of sacrificed individuals, all of which point to the symbolic importance the site must’ve had.

An attempt was made to cover the pyramid later in its life, perhaps marking a shift in political power or belief in the city, but thank goodness these carvings remain. And what a shame so many visitors don’t make it this far.

Like Pompeii in Italy, much of Teotihuacán remains buried and unexplored. The Avenue of the Dead that currently stops abruptly at the Citadel continued on in antiquity, surrounded by buildings large and small. One can only imagine what lies beneath…