Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula boasts some of the finest remains of the Maya, a Mesoamerican civilisaton who mastered architecture and astronomy and dominated Central America before the Spanish conquest. Uxmal, south of the city of Mérida, was our destination on a day that also included a visit to a derelict hacienda and two swimmable sinkholes known as cenotes.

Raul, our guide for the day, was a friendly Mérida local with a great depth of knowledge. He did a superb job of explaining the history of Uxmal and the Mayan people, as well as detailing the centuries of colonial rule that followed. He also navigated expertly the quiet but potholed roads of the peninsula, especially in the occasional downpours that drenched us during the latter part of our day out.

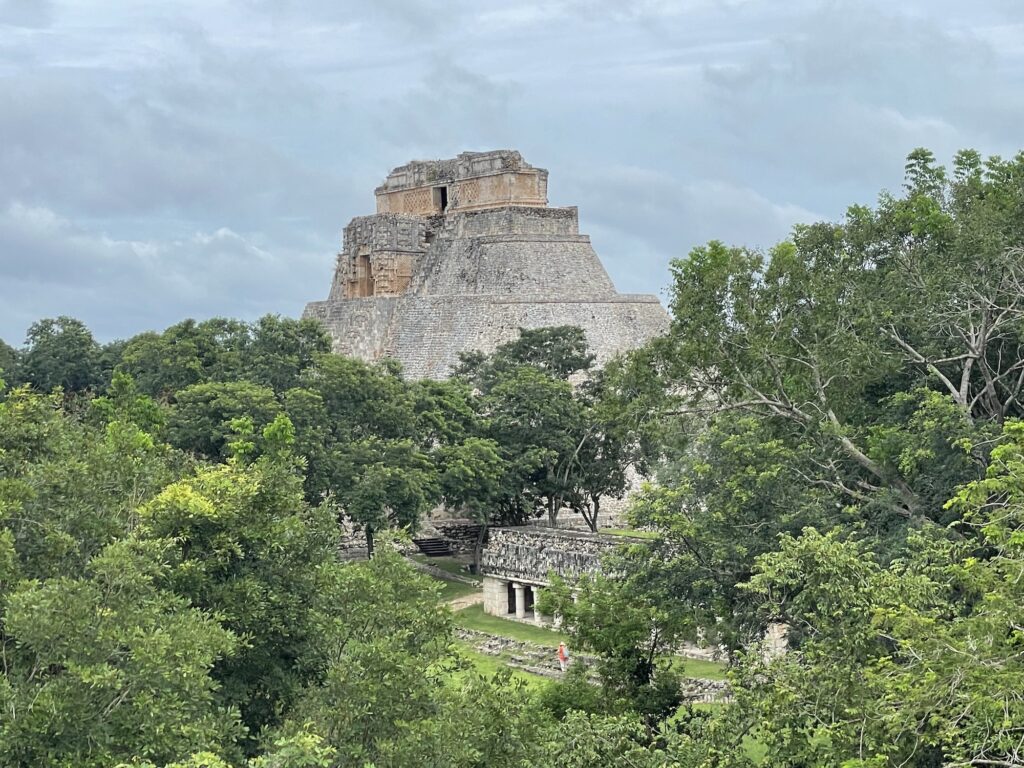

The Yucatán is not the most obvious spot for a civilisation to thrive. A limestone plateau without any surface rivers, it’s largely flat and with little in the way of soil to support farming, but the Maya made it work and the peninsula is peppered with their settlements and cities. Many, though, have long since been smothered by the encroaching jungle and are only now being revealed through new technologies such as LIDAR. Uxmal was ‘rediscovered’ by Europeans in the 19th century but excavation work, which continues today, only began seriously early in the 20th. It is an astonishing site, so much the better for being relatively free of crowds, its imposing buildings and pyramids standing majestically free of the jungle that is forever threatening to consume it.

Uxmal was settled for many years before the grand structures of the city were built from around 700AD. It clearly became an important civic and religious centre, with many references in the architecture to the rain god Chaac and other deities, but the population declined significantly in around 1200AD, perhaps as a result of climate change. It was largely abandoned with the arrival of the Spanish, who forcibly converted the Mayan people to Catholicism, away from the old beliefs.

The Pyramide el Adivino or Pyramid of the Magician provides a magnicent introduction to the site, the tallest structure in the complex. Beneath the pyramid are a series of smaller structures built one on top of the other over the centuries. Steep, featuring a number of temples and with rounded sides, it’s decorated with busts of Chaac and is a breathtaking work of art and architecture. Seeing it from elsewhere in Uxmal, soaring above the trees, is an unforgettable experience.

Next to the pyramid is what Raul described as the parliament but is otherwise known on the maps as the Nunnery Quadrangle. An expansive civic space with a large central square, it’s surrounded by grand buildings that are also decorated with reliefs of the gods, of Chaac and the feathered serpent. Remains of colourful murals are also evident in places. It’s possible that the square was where tributes were paid to the city and its leaders, and where key civic events played out.

We walked on past a ball court, where many would’ve gathered to watch the Mayan’s favourite sport, to an area that has only recently been excavated. It includes a road leading to a public square where trade may have been carried on. Beyond is another grand pyramid, although much of it smothered in vegetation during our visit.

Our final stop was at a structure that rivals the Pyramid of the Magician for impact, the Palace of the Governor. Not only is at another building decorated in beautiful carvings, a further illustration of the architectural prowess of the Mayan, but it also illustrates their knowledge of astronomy, which was far in advance of Europeans of the time. More than 320ft long, the palace stands on a terrace and would’ve been one of the most signficant buildings in Uxmal. One of the central entrances aligns with the planet Venus while other features are significant to and align with solstice events.

Uxmal will live long in my memory. A site of quite breathtaking architecture and history.

The Hacienda Mucuyché, some miles back toward Mérida, is a completely different experience and reveals another, bleaker side of the Yucatán. The arrival of the Spanish saw the advent of a network of ranches across the peninsula and, from the 19th century, the farming of henequen, which produced one of the toughest natural fibres on earth. It also brought massive profits for a few colonial families, who celebrated by building mansions in the European style in places like Mérida. When man-made fibres brought the end of the trade, many of these haciendas were abandoned and left to rot. The jungle took over. The villages that grew up around them often remained but today they look desperately poor and bleak, some of the residents living in little more than hovels.

Mucuyché was abandoned but was then purchased a few years ago to create a tourist attraction based on its particularly eye-catching cenotes. These are numerous in the Yucatán – sinkholes caused by the collapse of limestone bedrock to expose the groundwater beneath. Like others, it’s possible to swim in the ones at Mucuyché, but this is tourism done with a heavy dose of ruthless efficiency. There’s no going off piste but maximum peso extraction.

The tour began with a trot around the remains of the hacienda and the neighbouring factory that processed the henequen. This was carried out at such breathless speed that I only managed to catch every fifth word that the guide fired at us, admittedly in both Spanish and English. And while much was said about the wealth created by the trade and how the fibre was created, there was little about the exploitation of the workers and the resulting misery that was a notorious feature of hacienda life. We were then herded at speed into the changing rooms ready for our descent into the cenotes, which is really the main reason anyone visits Mucuyché.

Raul waited patiently while we were led down into the Cenote Carlota, named after the first and only Empress of Mexico, who allegedly took a dip in its deep blue, clear waters back in the 19th century. Our tour guide then led us through the waters, along a canal in a deep gorge into the underground Cenote Azul Maya – the star of the show. Stalactites hovered above the clear blue waters, illuminated by a few lights in the water and our guide’s torch.

It was incredibly atmospheric and wonderfully relaxing, which made up for the speed with which the rest of the tour was carried out. A perfect end to a busy, fascinating day.